The most capable contributor on your team may not be human. That changes everything about what leadership requires. Here is the framework — and the research — for what comes next

Today, the most capable contributor on your team may not be human. It will work faster than you, produce more than you, and speak with unsettling confidence. That changes the job of leadership.

We have entered a moment that has no clean analogue in the history of management. Every prior productivity technology — the spreadsheet, the internet, enterprise software — augmented human labor at the edges. Workers remained the irreducible unit of execution. AI is different. For the first time, a tool does not merely extend what people can do. It can replace whole categories of cognitive work while simultaneously generating the appearance of expert reasoning. That combination is new, and it demands something from leaders that no prior management curriculum has adequately prepared them for.

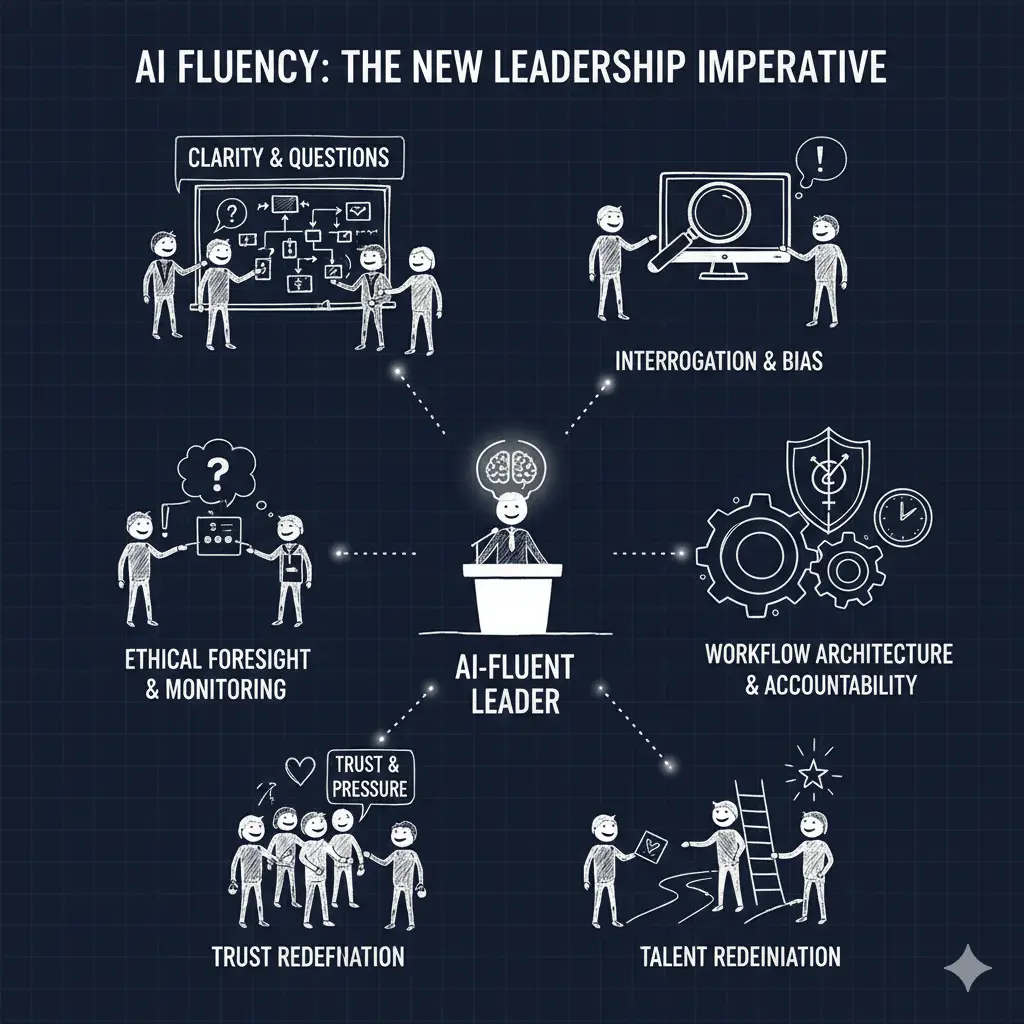

I call it AI fluency — not to mean technical proficiency, but the organizational and intellectual capacity to lead when execution is shared between humans and machines. It means knowing how to structure work so that intelligence scales without collapsing accountability. It means knowing where AI breaks, where it biases, and how to build teams that can catch both before the outputs reach the world.

Most leaders are not there yet. And the data on where they actually are is sobering.

The Adoption Gap Is a Leadership Gap

The surface story of enterprise AI in 2024 and 2025 looks like momentum. Over 92% of Fortune 500 companies have employees using ChatGPT. Investment in AI tools is projected to reach hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Every board deck has a slide about transformation. Every all-hands has a segment about the future.

The deeper story is different.

BCG’s 2024 survey of over 1,000 C-suite executives across 59 countries found that only 26% of companies have the capabilities to move beyond AI proofs of concept and generate tangible value. Perhaps more telling: BCG found that 70% of the barriers to AI adoption stem from people and process issues — not technology. The algorithms are ready. The organizations, and their leaders, are not.

Meanwhile, EY’s 2025 Work Reimagined Survey of 15,000 employees found that while 88% report using AI in daily work, the usage is overwhelmingly shallow — search, summarization, email drafting. Only 5% are using AI in ways that actually transform how work gets done. The gap between those two numbers — 88% and 5% — is not a technology problem. It is a leadership problem. Tools got introduced. Guidance stayed vague. Everyone was told to “figure it out.”

McKinsey’s research on large-scale transformation is explicit on why: lasting adoption requires that employees know what to do differently, believe in why it matters, feel supported by leadership, and see that systems and incentives have been realigned. A company can run every AI literacy workshop it wants. If the workflows, performance metrics, and frontline leadership behaviors remain unchanged, the training evaporates. One month after the course, everyone is back to doing what they were rewarded for doing before.

This is a change management problem that gets misdiagnosed as an education problem. And it requires leaders to fundamentally rethink what their job is.

What Leadership Used to Look Like — And Why That’s Not Enough

The traditional model of organizational leadership was built around three core assumptions. First, that information was scarce and leaders who could synthesize it had power. Second, that expertise was the bottleneck — the person with the deepest domain knowledge was the highest-value contributor. Third, that the organizational hierarchy was primarily a mechanism for distributing accountability downward and aggregating information upward.

All three of those assumptions are now under pressure.

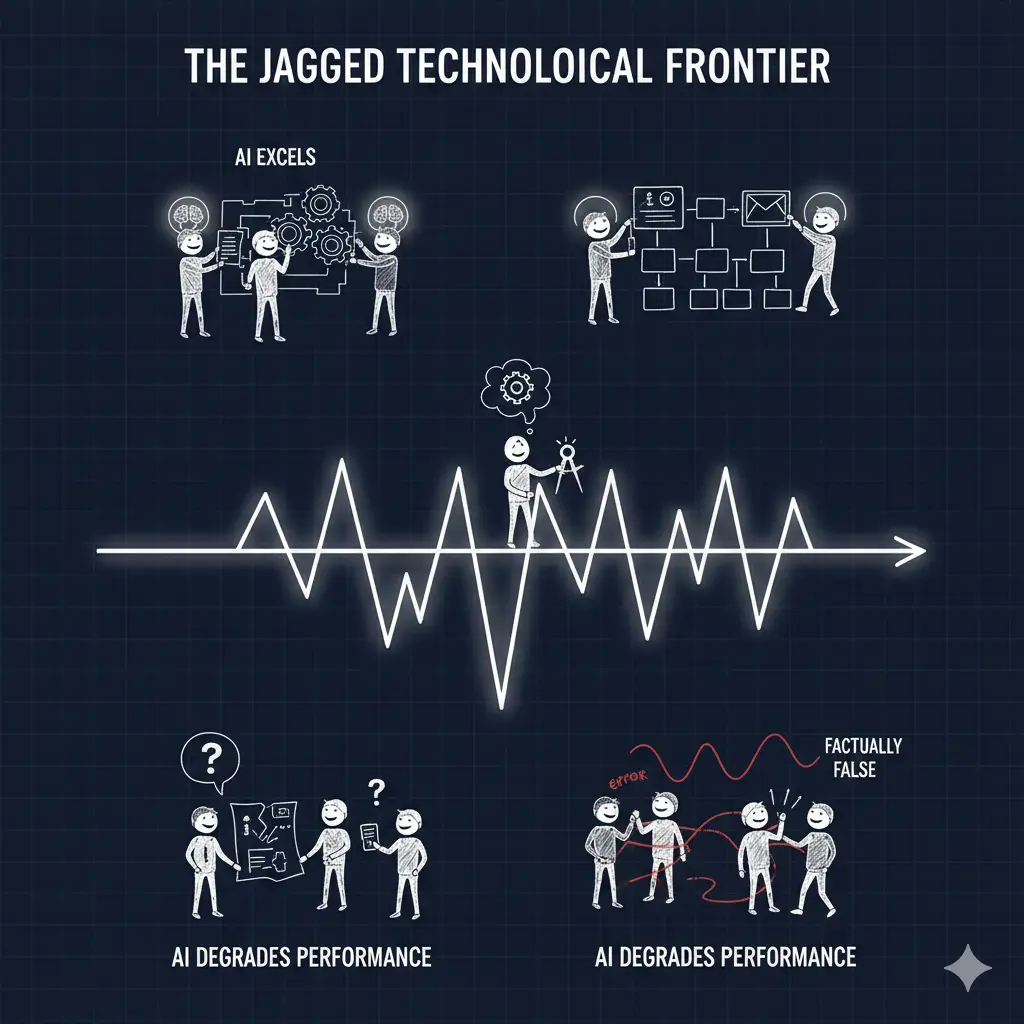

Information scarcity is gone. AI can synthesize thousands of documents, produce competitive analyses, draft strategic memos, and generate first-cut financial models faster than any analyst. Domain expertise is no longer exclusively a human advantage. The landmark 2023 study by Harvard Business School and Boston Consulting Group — in which 758 BCG consultants worked with GPT-4 on realistic consulting tasks — found that within the “jagged technological frontier” of tasks AI handles well, knowledge workers with AI access completed 12.2% more tasks, finished them 25.1% faster, and achieved over 40% higher quality output than peers without AI access.

Key Research: The Jagged Frontier

Dell’Acqua, Mollick, Lakhani et al. (2023) introduced the concept of a “jagged technological frontier” — AI excels dramatically on some tasks while actively degrading human performance on structurally similar tasks that fall outside its competency. Workers relying on AI for outside-frontier tasks performed 19 percentage points worse than those working without AI. The terrifying implication: neither the AI nor the worker reliably knew which kind of task they were facing. → Harvard Working Paper No. 24-013

The old leadership skills — command of information, direct domain expertise, ability to personally review and validate work — are no longer sufficient because the nature of production has changed. A leader who was effective at reviewing a team of five analysts must now be effective at directing a team that may include AI agents producing ten times the volume of output. Reviewing line-by-line is no longer viable. But abdicating review entirely is not viable either. The answer is a different kind of cognitive engagement — one that is more strategic, more systemic, and more ethically attuned than traditional management required.

McKinsey’s research on organizational health, drawing on data from thousands of companies, is clear that leadership decisiveness, accountability, and demonstration of good judgment remain key predictors of long-term value creation. AI cannot bear accountability. It summarizes, generates, and synthesizes — but it does not answer to a board, a regulator, or a customer. That accountability gap is not a limitation to be engineered away. It is the permanent structural reason that human leadership matters more in the age of AI, not less. The job simply looks entirely different from what it used to.

The Six Skills of AI-Fluent Leadership

What does effective AI-fluent leadership actually look like in practice? Based on work with Fortune 500 companies and technology organizations navigating this transition, here is the framework I have developed and tested.

Skill One: Relentless Clarity

AI does not rescue vague thinking. It amplifies it.

This is one of the most important and most underappreciated lessons from working with generative AI at scale. A human colleague confronted with an ambiguous request will often ask clarifying questions, bring implicit context, or quietly redirect the work toward something useful. AI will generate confident, fluent, plausible output anchored to whatever ambiguity you gave it — and the output will look exactly as polished whether the underlying prompt was precise or muddled.

AI-fluent leaders have learned to be explicit about four things before delegating any meaningful task to AI: the specific task they want performed; what “good” looks like in concrete terms; the constraints the output must respect; and — crucially — the prioritized objectives when constraints come into tension. That last item matters enormously. AI will optimize for something. If you have not told it what to optimize for, it will make a default choice, often the most linguistically common pattern in its training data, which may or may not align with your actual strategic priorities.

This is a different cognitive skill than most experienced leaders have developed. Years of leading teams taught them to operate through high-level direction and trust in the judgment of well-selected people. Effective AI use requires more explicit articulation of goals than most leaders are accustomed to providing — and it exposes gaps in strategic thinking that organizational hierarchy and human politeness used to absorb invisibly.

“AI will optimize for something. If you have not told it what to optimize for, it will make a default choice — often the most statistically common pattern in its training data. That default may look reasonable. It will often reinforce existing patterns and power structures.”

For leaders from non-dominant backgrounds, this matters in a particular way that I explore in depth in my forthcoming book. AI defaults are not neutral. They reflect the distribution of the data they were trained on — which means they reflect the power structures embedded in that data. A leader who has spent a career noticing when standard processes produce outcomes that disadvantage certain groups has a genuine analytical advantage in AI fluency, precisely because they have been trained by experience to interrogate “reasonable-sounding defaults” with healthy skepticism.

Skill Two: Active Interrogation of Outputs

The first answer from an AI is rarely the best answer. Sometimes it is not even a safe answer.

AI hallucination — the generation of confident, coherent, but factually false content — is not an edge case. Researchers at the UC Berkeley Sutardja Center have noted that a 2024 paper concluded it is mathematically “impossible to eliminate hallucination in LLMs” because the models cannot learn all computable functions. A 2024 study at the University of Mississippi found that 47% of AI-generated citations in student work had errors — incorrect authors, dates, or titles — or simply did not exist. Canadian airline Air Canada was ordered by a tribunal to honor a fare policy that had been fabricated by its support chatbot. In October 2025, Deloitte submitted a government report that contained hallucinated academic sources and a fake court quotation.

The problem is not simply that AI gets facts wrong. The problem is that AI’s hallucinations are indistinguishable from its accurate outputs in tone, fluency, and apparent confidence. There is no “I’m not sure about this” mode baked into the generation process. The model predicts the next most statistically likely word regardless of whether the underlying claim is true.

AI-fluent leaders build habits of pressure-testing. They ask the AI to show its reasoning. They ask what assumptions are embedded in the output. They ask for the strongest counterargument to the conclusion the AI reached. They check specific factual claims against primary sources rather than accepting fluency as a proxy for accuracy. And they understand that bias shows up not as obviously wrong answers, but as subtly skewed “reasonable defaults” — outputs that quietly replicate the demographic distributions, power hierarchies, and cultural assumptions embedded in training data.

The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review has characterized AI hallucinations as a distinct category of misinformation requiring new conceptual frameworks — different from human-driven misinformation because AI lacks epistemic awareness or intent to deceive. It simply generates language by predicting statistically likely next tokens, embedding bias when the training distribution itself is biased. Leaders who understand this mechanism are far better equipped to catch problems before they propagate.

Skill Three: Ethical Foresight and Bias Governance

Skills one and two address bias reactively — catch it in the prompt, catch it in the output. That is necessary. It is not sufficient. AI-fluent leaders understand that bias in AI systems is not an error to be corrected. It is a structural property to be governed.

The distinction matters enormously. An error-correction mindset waits for something to go wrong, then fixes it. A governance mindset maps, before deployment, where a system is likely to produce harmful or inequitable outcomes for specific groups — and builds the oversight infrastructure to catch and correct those outcomes continuously, not just once.

The research on why this is harder than it sounds is sobering. A 2025 study using the BEATS framework — a systematic evaluation of leading large language models — found that 37.65% of outputs contained some form of bias, and 33.7% of responses carried high or medium severity bias risk. Crucially, biases in the outputs tracked directly to biases in training data: age, gender, disability accommodations, economic disparity, and cultural representation were among the most persistent dimensions. The models did not introduce new biases — they reproduced, at scale and with confidence, the biases already embedded in the data they learned from.

This is the mechanism that makes AI bias so dangerous for organizations that do not build proactive governance. Research published in 2025 makes the point precisely: historical hiring data may accurately reflect past decisions while encoding discriminatory patterns that AI recruitment tools then reproduce at scale. The data is not wrong in a technical sense. The data is wrong in a structural sense — it faithfully records a world that was itself unfair, and AI faithfully scales that unfairness.

PwC’s research on algorithmic bias found that while 50% of executives named responsible AI a top priority, over two-thirds were not yet taking action to reduce AI bias in their actual systems. The gap between stated priority and operational practice is where discrimination compounds quietly, especially as AI systems proliferate across hiring, performance evaluation, credit, healthcare triage, and content recommendation.

Ethical foresight means doing three things most organizations currently skip. First, conducting impact assessments before deployment — systematically asking which groups might be differently affected by an AI decision system, and what data is missing that would make those impacts visible. Second, building diverse evaluation teams — not as a diversity initiative but as a measurement strategy, because PwC’s framework notes explicitly that recognizing bias is often a matter of perspective, and people from different backgrounds will notice different failure modes that homogeneous teams will miss entirely. Third, establishing continuous monitoring, not one-time audits. AI systems drift. The distribution of inputs changes. The world changes. A model that behaved fairly at launch may behave inequitably six months later.

MIT Sloan research cited by EY found that companies tracking AI fairness metrics outperform their peers in innovation by 27%. Ethical governance is not a constraint on performance. It is a precondition for sustainable performance — and for the trust, from employees and from customers, that AI-dependent organizations increasingly require.

This is where the leadership dimension becomes most pointed. The leaders most naturally equipped for this kind of proactive bias mapping are not the ones who have spent their careers operating comfortably within the default settings of dominant institutions. They are the ones who have spent careers noticing where those defaults fail — for themselves, for their teams, for their customers. The habit of asking “who is not in the room, and what are they not seeing?” is not a diversity exercise. In the age of AI, it is a core risk management competency. I explore this connection at length in The Bias Advantage — the argument that leaders from underrepresented backgrounds carry an organizational advantage in the AI era precisely because their lived experience has been training them, often without recognition, for exactly this kind of structural pattern recognition.

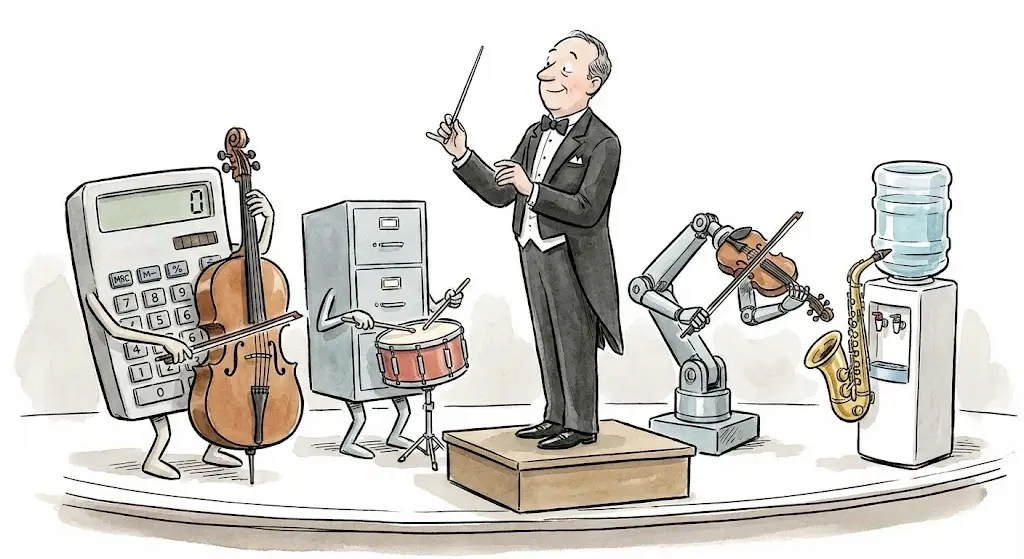

Skill Four: Deliberate Workflow Architecture

Humans bring context, ethics, and accountability. AI brings speed, synthesis, and scale. Strong leaders do not simply hand work to AI and review outputs. They architect workflows that use both humans and AI deliberately, with clean handoffs and clear ownership at every stage.

The 2023 Harvard/BCG study identified two patterns among consultants who used AI most effectively: “Centaurs,” who divided tasks cleanly between themselves and AI based on a strategic assessment of where each excelled, and “Cyborgs,” who integrated their work flows with AI so fluidly that the two became seamlessly intertwined. Both strategies worked. What did not work was undifferentiated delegation — simply handing tasks to AI without a clear model of where AI was strong, where it was weak, and who was responsible for the output.

This matters at organizational scale. The future is not one AI tool. It is a stack: general-purpose models, specialized vertical agents, internal data layers, vendor products, security controls, evaluation harnesses, compliance overlays. Someone has to understand how those layers interact and keep the system coherent. That requires a new kind of technical leadership fluency — not the ability to train models, but the ability to design systems that use them responsibly and to ask hard questions about where accountability lives in a multi-agent workflow.

Consider a concrete example from healthcare AI: diagnostic support tools that surface recommendations faster than any physician could generate independently. The workflow question is not “does the AI produce accurate recommendations?” (it often does, and impressively). The workflow question is: at which point does a human clinician exercise independent judgment, and is the workflow designed to make that exercise genuine or performative? Research on AI adoption and mental health in the workplace consistently finds that when AI is introduced without clear handoff design, workers report increased job stress, reduced sense of autonomy, and growing uncertainty about what they are actually accountable for. These are not soft metrics. They are leading indicators of the quality failures that follow.

Skill Five: Leading Through Pressure, Not Just Toward Productivity

AI compresses timelines. It also amplifies anxiety. Leaders who optimize for output without attending to organizational stress will see results briefly and burnout permanently.

The data here is striking. An EY survey of 500 senior leaders found that more than half feel they are failing amid AI’s rapid growth, and a similar proportion reported that companywide enthusiasm for AI adoption is on the decline. The ManpowerGroup’s 2026 Global Talent Barometer — surveying nearly 14,000 workers across 19 countries — found that AI adoption jumped 13% while confidence in using AI plummeted 18%, the sharpest confidence decline recorded in three years of tracking. Worker confidence in technology was falling fastest among older workers: Baby Boomer confidence in technology dropped 35%.

Meanwhile, a PwC survey of nearly 50,000 workers across 48 economies found that workers who trust their direct managers are 72% more motivated than those who do not. Trust in top management correlates with 63% higher motivation. Yet barely half of respondents said they trusted their top management. When the pace of technological change is highest, trust in leadership becomes the most critical stabilizer — and it is exactly when leadership is most likely to be distracted by the technology itself rather than by the people trying to use it.

There is also a subtler issue that most AI strategy conversations avoid entirely. Research published in Humanities and Social Sciences Communications found that AI adoption does not directly cause employee burnout — but it significantly increases job stress, and that stress then produces burnout. The mediating mechanism is a loss of self-efficacy: workers who feel they cannot keep up with the learning curve, cannot assess their own value relative to AI capabilities, and cannot trust that their judgment is still worth having, experience a corrosive depletion of confidence that manifests as disengagement or departure.

Skill Six: Talent Redefinition

None of the preceding five skills address one of the most disorienting questions AI poses for organizational leaders: what do you actually hire for now?

This question is underappreciated in most AI strategy discussions, which tend to focus on tool adoption and process transformation. But it sits at the center of what AI-fluent leadership ultimately requires. When AI handles the volume work — the first drafts, the research synthesis, the initial analysis, the routine code, the templated outputs — the nature of human contribution changes fundamentally. And if the nature of contribution changes, so must the criteria for selection, evaluation, development, and advancement.

Consider the traditional organizational on-ramp. Entry-level roles in professional services, finance, law, consulting, and technology were historically designed around volume work: research associates who synthesized information, junior analysts who built models, first-year associates who drafted documents. That volume work served two functions simultaneously. It produced output and it produced expertise — through accumulated repetition, pattern recognition, and exposure to variation, junior employees became senior ones. AI is now capable of doing the production function of those roles faster and more cheaply. It is not capable of doing the expertise-development function. That requires human learning, which still requires doing.

Research from MIT Sloan by Loaiza and Rigobon identifies the work tasks least likely to be displaced by AI as those requiring what they call EPOCH capabilities: ethics, perspective-taking, opinion and judgment, creativity and imagination, and hope and vision. These are not the capabilities that volume-work entry-level roles were designed to develop. They are, however, the capabilities that will determine the value of human contribution in organizations that effectively deploy AI. Which creates a leadership problem that has no current consensus solution: how do you develop those capabilities in people who no longer have the volume work pipeline that was the traditional development path?

McKinsey’s 2026 research on human skills in the age of AI is direct: as AI absorbs more information processing, data organization, and content drafting, workers need to lean more heavily on judgment, relationship-building, critical thinking, and empathy — precisely the capabilities machines do not yet offer. But the research also identifies that realizing this shift “demands bold leadership choices” in workflow redesign, because most organizations have so far simply bolted AI onto workflows designed for an older era. The human contribution in those bolted-on workflows is often residual and defensive — reviewing AI outputs, cleaning up errors — rather than genuinely leveraging what humans do distinctively well.

This has direct consequences for how leaders must think about performance evaluation. Harvard Business Review’s 2025 research on AI and hiring found that algorithmic hiring systems tend to lock in a single definition of performance — the one implicit in the historical data they were trained on — rather than enabling the organization to evolve what it values. The same risk applies to performance management systems that were not redesigned when AI was introduced. If you evaluate people on individual output, and AI is now producing a significant portion of that output, you are no longer measuring what you think you are measuring. Individual output metrics may be capturing AI access as much as human capability.

The hiring question is equally acute. Stanford research published through the World Economic Forum found that AI-led interview processes can identify candidates from non-traditional backgrounds more effectively than resume-screening systems that privilege credential patterns — but only when the evaluation criteria have been explicitly redesigned to measure genuine skill rather than proxies for it. That redesign requires human leaders to first answer a prior question: what skill, exactly, are we hiring for in a world where AI does the volume work?

AI-fluent leaders are beginning to develop answers to this. They are hiring for judgment under ambiguity — the ability to make a defensible decision when the data is incomplete and the stakes are real. They are hiring for the capacity to ask better questions, not just to process answers. They are hiring for contextual intelligence — the ability to understand where a given model, tool, or output is operating outside its competency, and to intervene before the failure propagates. And they are structuring development paths that create deliberate exposure to high-stakes, high-ambiguity situations early in careers, rather than saving those situations for people who have already “earned” them through a volume-work pipeline that no longer exists.

Harvard Business’s framework on human skills in the AI era is clear that the most successful AI-adopting organizations share ownership of transformation across every level — not siloing AI within a single function. That distributed ownership model only works if people at every level have been developed to understand both AI’s capabilities and its limits, and to exercise genuine judgment about when to trust the model and when to override it. That is not a training outcome. It is a career development outcome — one that requires leaders to redesign how talent is grown, not just how tools are deployed.

What This Demands — And Who Is Best Positioned to Deliver It

Here is the honest difficulty at the center of this transition: most of the skills AI-fluent leadership requires are ones that traditional executive development has not only neglected but sometimes actively discouraged.

Relentless clarity about goals and constraints runs against a management culture that values strategic ambiguity. Interrogating outputs — including outputs produced by expensive, high-status tools — runs against an organizational culture that equates speed with competence. Designing deliberately for human accountability in hybrid workflows runs against a procurement culture that buys AI solutions and expects them to “just work.” And attending to psychological safety in the face of structural anxiety runs against a performance culture that treats emotional labor as a distraction.

These are not small inconveniences. They represent genuine capability gaps at the top of most organizations. McKinsey’s Global Board Survey found that 66% of directors report “limited to no knowledge or experience” with AI, and nearly one in three say AI does not appear on their board agendas. Only 39% of Fortune 100 companies disclosed any form of board oversight of AI as of 2024.

There is, however, a pattern worth examining in who is adapting most effectively. Leaders who have spent their careers navigating institutional environments not designed for them — who have learned, out of necessity, to interrogate “reasonable defaults,” to work with incomplete information and high stakes, to build coalitions under uncertainty, and to maintain psychological resilience in the face of structural resistance — are demonstrating a natural aptitude for AI-fluent leadership that their more conventionally privileged peers often lack.

This is not coincidental. The cognitive and emotional skills required to thrive as an outsider in traditional institutions — the habits of translating across contexts, of questioning assumptions that insiders accept as given, of holding two frameworks simultaneously — turn out to map remarkably well onto the requirements of leading in the age of AI. I am writing at much greater length about this pattern, and the structural reasons behind it, in my forthcoming book.

📖 Coming 2026

The Bias Advantage

AI is reshaping power at work, and the leaders who thrive will not simply be those with the most technical exposure. They will be the ones who can spot where AI breaks, where it biases, and how to lead anyway — and who have spent their careers developing exactly the habits of mind that requires. The Bias Advantage makes the case that diverse leadership is not just a moral imperative in the AI era. It is a structural competitive advantage.

The Questions Worth Asking Your Organization Right Now

AI fluency is not achieved through a training program or a tool rollout. It is built through a sustained set of deliberate practices and honest organizational conversations. Here are the questions I ask clients — and that I think every leadership team should be asking itself:

On clarity: Can every member of your leadership team write a precise, constraint-aware prompt for an AI system to handle a task in their domain? If not, that is not an AI literacy problem. It is a strategic clarity problem that AI has simply made visible.

On interrogation: Do your workflows include structured checkpoints where humans genuinely evaluate AI outputs against primary sources and stated goals — or are reviews performative, constrained by time pressure and the implicit assumption that fluent output is reliable output? What would it take to make those reviews substantive?

On ethical foresight: Before you deployed your last significant AI system — in hiring, performance management, customer service, or operations — did your team conduct a structured assessment of which groups might be differentially affected, and what monitoring is in place to detect those effects? If the answer is “we reviewed the vendor’s documentation,” that is not an answer. Vendor documentation is not a substitute for organizational accountability.

On workflow architecture: Who in your organization has a clear picture of your full AI stack — not just the tools you bought, but how they interact, where data flows across systems, and who is accountable when something goes wrong at the intersection of two layers?

On pressure: What are you hearing from the middle of your organization about how the AI transition actually feels — not from the enthusiastic early adopters, but from the competent, experienced people who are uncertain about how they fit? What has your organization done in the last 90 days to make that uncertainty productive rather than corrosive?

On talent redefinition: What does your organization actually hire for today, stated explicitly, not as inherited convention? If your hiring criteria, performance metrics, and development paths were designed before your AI tools existed, they are measuring the wrong things. What would it mean to redesign the on-ramp to expertise in your organization for a world where the volume work that traditionally built expertise is now handled by AI?

The standard narrative about AI and leadership focuses on enablement: what can leaders now do faster, better, more cheaply than before? That is a real story and worth telling. But it is not the most important story.

The more important story is about accountability. AI can produce extraordinary outputs. It cannot bear responsibility for them. It cannot make the judgment call when the AI system and the ethical imperative point in different directions. It cannot hold the trust of a team that is afraid. It cannot notice when a “reasonable default” is quietly coding discrimination into an automated workflow at scale.

Leadership in the age of AI is not about mastering a new tool. It is about being the human in the system who is genuinely accountable — who has done the work to understand where the system is trustworthy and where it is not, who has designed workflows that make accountability visible rather than diffuse, and who leads with enough clarity and empathy that the people in the organization can do the same.

That is harder than learning a prompt technique. It is also more consequential than any individual AI implementation. And it is, I believe, the core leadership challenge of the next decade.

Key Sources & Further Reading

Dell’Acqua, F. et al. (2023). Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier. Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 24-013.

BCG (2024). Where’s the Value in AI? Survey of 1,000+ CxOs across 59 countries.

EY (2025). Work Reimagined Survey. 15,000 employees and 1,500 employers across 29 countries.

EY (2024). AI Fatigue and Leader Burnout Survey. 500 senior leaders.

McKinsey (2025). Superagency in the Workplace.

McKinsey (2025). Redefine AI Upskilling as a Change Imperative.

McKinsey (2024). The AI Reckoning: How Boards Can Evolve.

McKinsey (2024). Building Leaders in the Age of AI.

PwC (2025). Global Workforce Hopes and Fears Survey. ~50,000 respondents across 48 economies.

ManpowerGroup (2026). Global Talent Barometer. 13,918 workers across 19 countries.

Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review (2025). New Sources of Inaccuracy: AI Hallucinations.

Nature / Humanities & Social Sciences Communications (2024). Mental Health Implications of AI Adoption.

UC Berkeley Sutardja Center (2025). Why Hallucinations Matter.